Wood structure. 9' x 9' x 9'. In 2012 show "Figures and Grounds" at The Arts Club of Chicago.

Graduate thesis. A Consolidated Railway Station for Chicago, 1968. Photograph: Richard Nickel.

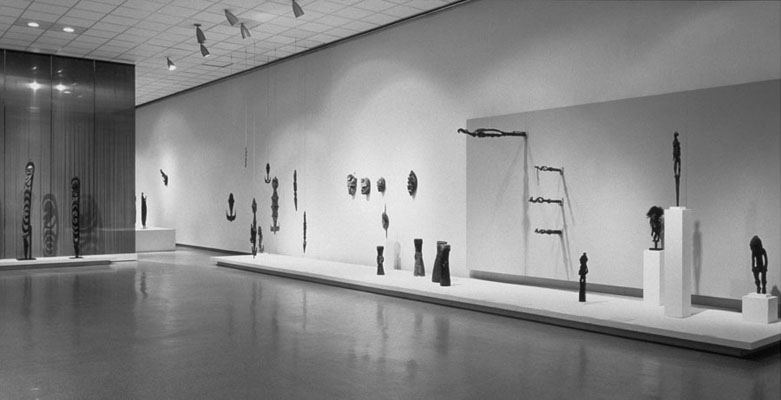

Exhibition design, Art of the Sepic River, 1971, Art Institute of Chicago, Vinci/Kenny Architects.

Reconstruction of the Louis Sullivan stock exchange trading room, 1976, Art Institute of Chicago. Vinci/Kenny Architects.

Yale University Art Gallery, museum store, 1984

Viennese Silver, exhibition design, Neue Galerie New York, 2003

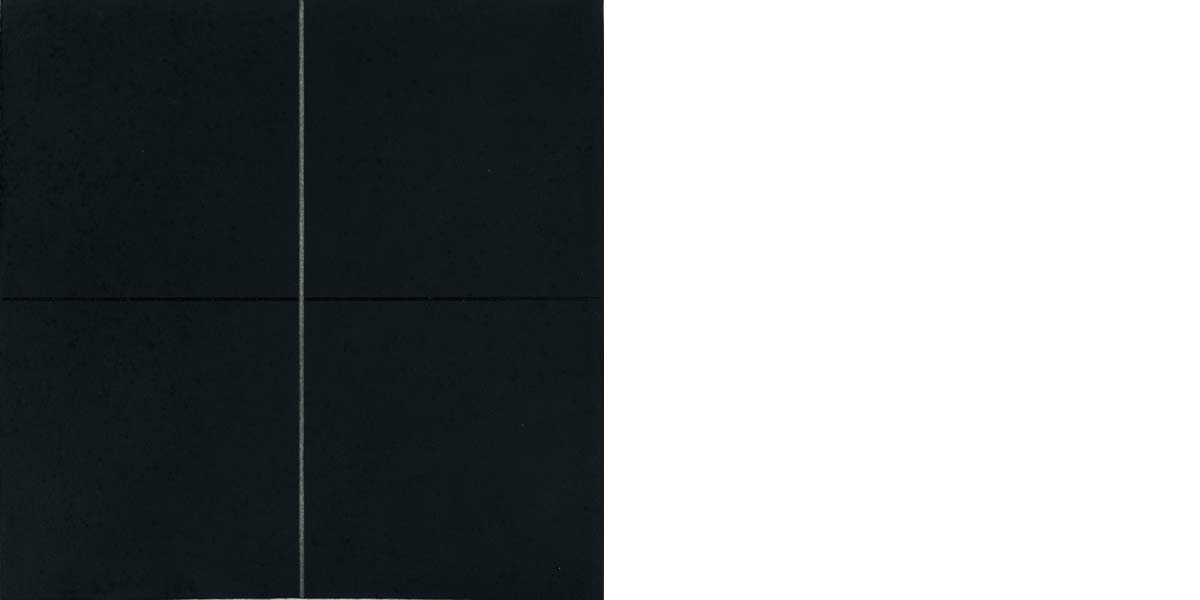

Pastel, powdered pigment, acrylic fixative on paper, 1974, 8" x 8"

Pastel, graphite, charcoal, acrylic fixative on paper, 1974, 8" x 8"

Graphite, charcoal, oil pastel on paper, 2012, 8.75 x 13.375 in.

Left, 80 Wooster Street. Right, Bladed door to Maciunas's loft in 80 Wooster Street.

Section drawing, ink on mylar, 1983, showing a 1976 installation at the Clocktower Gallery. For the book Michael Asher, Writings 1973-1983 On Works 1969-1979, written by Asher in collaboration with Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, editor.

Bottom left: I'm on a cornice measuring. Top left: Michael showing me where he took the picture from. Bottom right: I'm scrambling on to the roof. Top right: Michael.

Gila River cliff dwellings, 1275-1300, near Silver City, New Mexico. Mogollon culture.

Clarke House, 1919-1921, Santa Fe Springs, California. Irving Gill, architect.

Villa Tugendhat, Brno Czech Republic, 1928-1930. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, architect.

McMath-Pierce Solar Telescope, Kitt Peak Arizona, 1960-62, architect Myron Goldsmith: Partner, Skidmore Owings and Merrill, Chicago. The angled shaft is parallel to the earth's axis of rotation and extends into the earth.

ARCHITECTURE

I was raised in and around New York City. From childhood I was drawn to art and architecture. I decided to go into architecture and studied the subject with that intention, eventually discovering the program at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago developed by Mies van der Rohe. There I received Bachelor and Masters degrees. In graduate school I studied with the architect Myron Goldsmith and the structural engineer Fazlur Khan. I received scholarships from The Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, The American Iron and Steel Institute and an anonymous grant. After graduation I spent a year at Skidmore Owings and Merrill working with Goldsmith on a city plan for Columbus, Indiana. The structure developed for my Masters thesis was used by SOM as the basis for two projects — a submission (unbuilt) for the US Pavilion at the Osaka World’s Fair (1967) and the Central Facilities Building for Baxter Laboratories in Deerfield Illinois (1975).

In 1970 architect John Vinci and I formed the office of Vinci/Kenny. Our practice included many art installations and remodelings for museums, galleries and collectors, among them The Art Institute of Chicago, The Renaissance Society at the U of C. and the Smart Museum. We worked on many preservation and adaptive reuse projects such as H. H. Richardson's Glessner House, and Frank Lloyd Wright's Robie House. We were the architects for the reconstruction of the Louis Sullivan Stock Exchange Room at the Art Institute of Chicago. Our residential work included the Freeark House in Riverside Illinois and many remodelings and interiors. In 1974 I spent a year in New York working as an artist. I returned to Chicago for three years before moving permanently to New York in 1977. There I continued to practice architecture, working at art when I could.

In New York I worked briefly as a project architect at Marcel Breuer Associates. From 1980 I practiced independently or in collaboration with other architects on residential and institutional projects including the renovation of the Beaumont and Newhouse Theaters at Lincoln Center and a museum store for the Yale University Art Gallery. I worked on art exhibition designs for the Neue Galerie New York, two with John Vinci: the inaugural exhibition (2001) and the Dagobert Peche exhibition (2002). And two on my own: Viennese Silver, Modern Design 1780-1918 (2003) and Comic Grotesque: Wit and mockery in German art 1870 to 1940 (2004). In 2005 I scaled back my architectural practice and in 2008 closed it. Art became my sole occupation.

ART

My interest in art paralleled that of architecture. In my teens I attended several painting and drawing studios, once over a summer at the Art Student’s League, all very traditional. But it was the museums of New York that were my true school. My interest was polymorphic — unchanneled, undifferentiated, steeped in the pure pleasure of it all. The Museum of Modern Art was the most visited where I went not so much to learn as to be nourished. I grew into my time through its art as much as anything else.

In 1974 I rented a space in New York at 84th and Broadway where I worked as an artist for a year. That space — with asides to museums and galleries — was my art world. I started with no agenda, no theory and no specific influences. Eventually I evolved a technique on paper using dry media applied in successive layers, each layer fixed with a clear spray, altering the physical and visual ground of succeeding layers. What emerged were mostly abstract all-over fields which now seem inevitable, isolated as I was. Foremost was the process of making the work and the physical qualities of the materials, not their expressiveness. I worked using simple tasks requiring judgement but no artistic touch. Each drawing was something of a discovery. A desire to depersonalize the work came naturally and has been a constant throughout my career. The last weeks in the studio, using the same materials and techniques I had developed earlier, I made drawings with flat monochromatic fields, most with a vertical and/or a horizontal line bisecting them.

Through a friend I was able to show this work to Martha Beck, then an assistant curator at MOMA and later founder of the Drawing Center. She wrote out a short list of galleries I should contact, including Bykert, Leo Castelli, Paula Cooper and John Weber. Encouraged by my reception, art became a preoccupation.

It was not until 1988 that I again concentrated on art. Before then two events clarified my practice: First, a 1977 show at the Art Institute of Chicago organized by the then curator Anne Rorimer of recent European art. Among others, it included work by Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, Gerhard Richter and three Arte Povera artists: Giovanni Anselmo, Mario Merz and Gilberto Zorio. Their work was both quotidian and particular, qualities I valued. Second, in 1983 having many long conversations with the Los Angeles artist Michael Asher. We met when I was asked to make drawings for a book by Asher, edited and co-written by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh. We were of the same generation with overlapping interests: an artist interested in architecture, an architect interested in art. We both understood the essential difference between them: one expansive the other circumscribed. This made our exchanges easy. It was a fortuitous meeting for me. I had not attended art school and consequently had no acculturation in the field and few contacts. But by instinct or experience, my thoughts aligned with Michael’s in important ways. I came away from our conversations with confidence that I could work seriously as an artist.

From 1988 to 1992 I worked primarily on art, generating an enormous number of ideas which I recorded in drawings, models, photographs and texts. Few were developed into finished works at the time (or ever will be), but this work became a trove that I still refer to. In 1988 I began an association with the non-profit Lower East Side gallery ONETWENTYEIGHT, founded and directed by the artist Kazuko Miyamoto, where I have shown numerous works over the years. Since 2009 I have leased a large studio in Brooklyn which has allowed me to develop and produce work at a scale not possible before. Some of this work was exhibited in the 2012 show Figures and Grounds: Approaches to Abstraction, at The Arts Club of Chicago, guest curated by Anne Rorimer.

My work has broad connections to its time. Particular connections can become explicit during its development. I wish to originate ideas not simply mediate them. Genre and presentation are conditional to each project. Some things are discoveries as much as inventions; examples not assertions. Things can come easily or take years to develop. It is rarely programmatic, almost always non-objective, often serial, and can use text. Geometry has little intrinsic meaning for me but is something I am proficient at. What I say about what I do goes to means not meaning.

The autonomy of architectural vis-à-vis artistic practice, something I had always understood reflexively, was manifest at IIT. At the core of the curriculum was the art of construction: tectonics. First the basics were taught — delineation, visualization, materials, detailing, construction, structure, planning — and not until the last two years of a five year curriculum did anything resembling what is usually thought of as design enter the studio. These basic skills were used to encourage an open egalitarian architecture with a craft-like anonymity and inherent aesthetic merit. The auratic presence of a self-regarding designer would thus, it was hoped, be forestalled, freeing the work for the uncontested use of others.

In profound contrast, art, unconstrained by the desires of the social commons and the demands of utility, by presenting the possibility of freedom itself, all but compels it.

Mies was once asked by a student why his buildings were better than those of other architects whose work was similar. He said: "Because I have a good eye." How should this be understood? Was he being self-effacing, saying that it was the fitness of the practical and necessary choices an architect makes that is the primary determinant of the success of a building, the eye being secondary; or was it that despite all the similarities between one building and another, a good eye can make a very important difference? I would be tempted to say that the eye matters most when it matters least, for the architect and the artist.

I had an intense and unrepeatable encounter with the work of Gerhard Richter when for the first time I walked into a museum filled with it. My response was instant and unmediated. The following has been edited from a 1988 attempt to capture the intensity of that first encounter:

On entering the gallery the temperature seemed to drop to zero. The paintings appeared distant, many with paint drawn across them like a membrane as if sealing them off from human contact. Images were often the last in a series—an obscuring of a painting of a projection of a reproduction of a photograph of a person, place or thing, at each stage the image receding further. Light itself seemed weakened, as if the atoms of paint like minute beacons, were signaling from a vast remove. Richter works at the boundary of the self facing the terrible otherness of the external world.

I have exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, 1975; NYU’s Square East Galleries, 1993; 55 Mercer Gallery, 1999; Arts Club of Chicago 2012; the Schelfhaudt Gallery at the University of Bridgeport 2015, and in many group shows at the Onetwentyeight Gallery, 1988—2019; The Rhona Hoffman Gallery, 2019 (A work from the show was bought by an ex-director of a major museum). A piece was purchased for the Sol LeWitt collection in 1990. My architectural work has appeared in many publications.

A FORESHADOWING

I have unusual visual/spatial aptitudes, probably inherited from my mother. She came from a family with a long line of carpenters, builders and architects. Her father, Rollin Schellenger, made an uncertain living designing and building vacation houses and resorts in New England and the Adirondacks beginning around 1900. He had a generation older half-brother, Gilbert A. Schellenger, who became a successful architect in New York City designing mostly residential and commercial buildings. What little my mother knew of him was all I knew. But as I learned more of his life I discovered there were uncanny correspondences with mine.

We both went to Chicago to learn our craft, he from Ogdensburg in northern New York State to work in it after the great fire of 1871, me from New York City to study it in school. He settled permanently in New York City around 1882: I returned in 1977.

I live in an ordinary brownstone that my sister had once owned and where for several years three generations of us had apartments. To our amazement we discovered that it was designed by our great uncle! It was the only building by him that I knew of at the time, but as I eventually learned, he was the architect of many more both in the neighborhood and in other areas of Manhattan and Brooklyn developed in the last decades of the 19th century.

I learned from a 1992 article in The New York Times that he was the architect of 80 Wooster Street which long after it was built became notable for its occupant, the Fluxus artist and “Father of SoHo”, George Maciunas, who converted it in 1967 to the first artist co-op. He, with Jonas Mekas whose Cinematheque occupied the ground floor, made it an epicenter of the contemporary art scene. 80 Wooster Street, an unremarkable building but for its brief art world significance, seemed a mirror of my evolution from architect to artist.

AN AFTER THOUGHT

In 1976 Michael Asher did an installation (or de-installation) at the Clocktower Gallery on lower Broadway which consisted in the removal of all its windows and doors. The gallery had three levels. I had started a drawing for his book using material I had been given that documented only the interiors of the bottom two. It became clear that more context was needed. The drawing grew to include all three levels of the gallery and their contiguous exterior spaces, plus the clock room and bell loft.

Michael and I met there at least twice to document these. On the last day, we arrived at the building and found the gallery closed, a problem because there were crucial dimensions I had expected to get from inside. This was the only unfinished drawing and a deadline loomed. I wanted to leave with all the information I needed to complete it. What to do? There was a cornice that ran along the outside of the building which appeared structurally sound and wide enough to allow access to a gallery window from where I could get the needed measurements. But it would require climbing down from the roof to the cornice, skirting a projecting corner pilaster, and crawling to a window, this in an unprotected space between a wall and a two hundred foot drop… and returning (I’m not free from acrophobia).

Expedience overcame fear. As I was busy measuring I heard something overhead. I looked up to see an arm extended through a balustrade with my camera at the end of it. Michael was photographing me. I continued measuring and when finished made my way back to the roof where he was ready, camera in hand, to record that hoped for event.

What's fair is fair. Gaining possession of the camera, I asked Michael to show me where he took the first picture from and took one of him, and another a little later which caught him by surprise.

It would have been an unremarkable day had the gallery been open: no call and response, no pictures recording it, no suppressed panic. It seems a finality not only to what we did then but to all our give-and-takes — a closing down, a mixing of past and present, presence and absence, a confounding of time.

Michael died in 2012.

EPILOQUE: ARCHITECTURE

Theory precedes practice: practice informs theory.

When architecture imitates art it can easily become oppressive.

At Reims Cathedral one is amazed by what can be done with stone: at Vézelay Abbey one is amazed by the stone.

A formal or technical analysis could describe a building, but a deeper understanding would require not just a consideration of the building itself but of its relation to the society to which it bears witness both in resistance and acceptance.

Demanding that art serve an instrumental or functional purpose can diminish the freedom it requires to do its work. Architecture, on the other hand, exists precisely in order to satisfy a practical need. Whatever aesthetic charge architecture may at present be capable of will result directly from the way this need is satisfied.

With the will to do so it is easier to make good architecture than good art: let the needs of the project guide the solution, work impersonally and clearly, and build well. Resist making a statement. Then, whatever else the building may be, it will possess clarity and conviction which are usually not only enough but in this age often a great relief.

Wittgenstein, whose architectural work I admire, is reported to have said that the people who built the Georgian houses of Dublin, which he admired, had the good sense to know that they had nothing important to say and didn’t try. The many constraints on architecture have always made it an intractable medium. At the moment it is an unusable one, often devolving into spectacle and solipsism when used as such. The result is work that is numb to the feel of things, deaf to the bass-tone of existence. Its most annihilating criticism comes from a position of social and cultural enlightenment that judges it by what it is, not by what it wishes to be.

A project should be approached with alertness to its possibilities and limitations and with humility before the facts. Architecture is an art of opportunity. The most fruitful ideas come from an immersion in practical work. By paying close attention to the task at hand, a building will record in its substance the events, means and circumstances of its realization which, by a sort of calculus of the real, sums up a state of affairs and fixes it as a material fact. Whatever authentic values beyond the practical that may still be expressible in architecture will be circumstantial and result from subtle, specific, objective solutions that are an unfolding of emergent architectural qualities that are real, not superimposed. In this way, a building can point beyond the occasion of its making to become an object of interest and perhaps indirectly and fortuitously, a model of resistance, a place where each part would be entirely itself yet confirming the whole.